~ How my thoughts are running these days ~

Dad’s explosive sneezes would scare the shit out of all of us. They came out of nowhere and were unspeakably loud. Even the pets would jump.

When I was little, he called me Tiger Lily. As I grew up, he switched to Kelly-My-Darlin’. He’d wanted to name me Sioux, but my maternal grandfather put the kibash on that.

Years ago, on what was meant to be a catch-and-release fishing excursion, dozens of enormous barracuda surrounded Dad’s boat as soon as we anchored. Each time I hooked a fish, a barracuda struck. After I pulled in my third or fourth fish head, Dad – who knew how horrified I was to be an accomplice to this slaughter – glanced at me with a mischievous half-smile and grumbled, “Kelly, stop getting blood in my boat.”

His oft-repeated lessons:

- Do your best at all times in all things.

- If you say you’re going to do something, do it. You’re only as good as your word.

- Don’t hate. It takes too much energy.

He would calm fussy babies by placing them on his chest. We have so many photos of him like that – on the couch, eyes closed, with a tiny, sleeping bundle nestled right below his chin.

During a family road trip, after my sister, mom and I had played the alphabet game, I Packed My Grandmother’s Trunk, and who knows what else to pass the time, Dad suggested, “How about we play a game that’s absolutely silent?”

Last fall, he asked my husband and me to grab buckets and get in the car. Mom gave us a wide-eyed look like: Oh, just you wait and see! He drove us to the lot where his boat and trailer were parked. The boat cover had been weighted down by a recent rainstorm, and in the resultant pool were thousands of tiny tadpoles. Dad explained that he’d come by earlier to dump out the water, but when he saw the tadpoles, he had to change plans. Mom, Dad, JR and I spent the next half hour gathering tadpoles in buckets and relocating them to a nearby lake. Our little field trip didn’t surprise me at all. There’s no way in hell Dad would’ve dumped all those tadpoles onto the asphalt to die. He never would’ve even considered such a thing.

Dad once told me, “Life may be shit, but death is nothing.” I’m usually grateful to have been raised without religion or afterlife ideas, but not now. I wish I could believe we’d be reunited one day. Sometimes, when I remember he’s dead, it’s hard to breathe. I have to sit down. The pain roars through me like my blood is on fire.

He loved to dance. He used to take me to the father-daughter square dances when I was in Brownies. I adored those events. He loved Elvis, oldies, jukeboxes, and sharing the story of my grandfather telling him, after they’d traveled together in the car for a few hours, “Your music makes me puke.”

He was a brutal editor of my first book. “Why is everyone in this book always grinning and exiting? Why can’t they just smile and leave?” I was appreciative for the candid critique, but not so much for all the times he’d describe a critically-acclaimed book he’d disliked, proclaiming, “It was even worse than yours.” Each time, Mom would implore him to stop saying that, and he’d reply, “What? I’m saying this guy’s published and got all these great reviews, and his book is even worse than hers. So there’s hope!”

When I was in high school, he’d leave work early to come watch my tennis matches. There were all these people around the court in athletic clothing and this one tall, intimidating guy in a suit. His presence made me feel nervous and important at the same time.

On my dresser, there’s a photo of him from his Merchant Marine days. Hanging off the side of the frame is a slingshot he made when he was a boy. When I first set that up, I realized it would be a memorial someday. Now it is. I hate that.

He got to teach his grandson to ride a bike last summer. He was so thrilled. Mom has a video of him whooping with excitement as the new bicyclist goes whizzing by.

I hear his voice. I see his shimmering fingers as he explains something he’s excited about. I feel his hand holding mine. As a child, I would lay on his chest and listen to his heart – that stupid, broken heart that quit and stole my father from me. From all of us.

Sometimes I think I might get through a whole day without crying, then I cry at the very thought. It would’ve hurt Dad so much to see me this way. He wanted his loved ones to be happy. He would want us to be laughing.

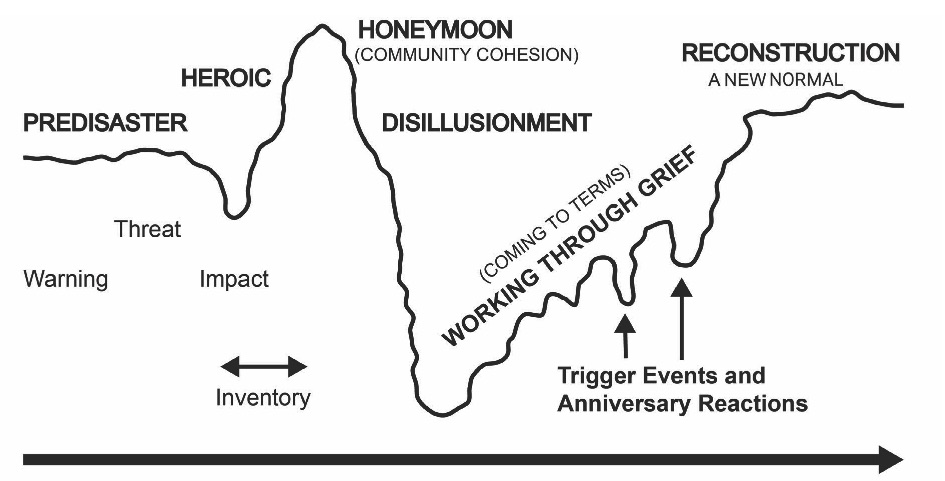

Years ago, I told my sister that when our parents died, I would never get over it. I know that’s true. Losing Dad will be a lifelong sorrow. Still, I look forward to a time when memories of him bring comfort rather than pain. That’s what people say, right? Find comfort in your memories. So I have to believe that time will come. For now, though, I just remember, and cry, and remember, and cry, and remember.

[While I still can’t believe the words “obituary” or “funeral home” have anything to do with my father, Mom did write a beautiful obituary for him that is now posted on the funeral home’s website. You can find it here.]